Understanding Brand Architecture: Structure That Scales

Most founders think about brand architecture like they’re organizing a family tree. Parent brand at the top. Sub-brands underneath. Products at the bottom. Clean. Simple. But, unfortunately, wrong.

Brand architecture isn’t about drawing org charts – it’s about building infrastructure that lets your brand IP scale without fragmenting. It’s the difference between Disney, which built a $200B universe where every property (Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars) reinforces the magic, and companies that acquire brands only to watch them lose coherence and value.

Brand architecture defines how your company’s portfolio creates equity. It’s the strategic framework that determines whether your brand portfolio compounds value or creates confusion. Whether partnerships strengthen your positioning or dilute it. Whether you’re building a brand ecosystem or managing a collection of disconnected assets.

This guide explains what solid brand architecture actually is, why it determines whether your brand scales or splinters, and how to structure your portfolio for long-term brand equity – not just short-term clarity.

What is brand architecture?

Brand architecture is the strategic framework that organizes brands, sub-brands, products and services within a company’s portfolio. It’s not an organizational chart. It’s ecosystem infrastructure – the structural foundation that determines how your IP scales across touchpoints without losing coherence.

Think of it like city planning versus random construction. A city with clear infrastructure – roads that connect, zones that make sense, systems that scale – thrives. A city where buildings pop up randomly, with no connection or plan, creates chaos. The same applies to managing many brands.

When PUMA partnered with Red Bull Racing, Porsche Design, and BMW Motorsport, those collaborations didn’t fragment the brand. They reinforced it. Why? Because PUMA’s brand architecture was built to accommodate partnerships across motorsport, fashion, and performance – all laddering back to athletic innovation. The architecture created guardrails: what fits, what doesn’t, how each partnership connects to the master brand’s IP.

Brand architecture guides everything from product naming to partnership decisions to acquisition strategy. It answers: Does this sub-brand operate independently or under the main brand? When acquiring a company, should it be rebranded or preserve existing brand equity? How can brands expand into new markets without diluting what they’ve built?

Without architecture, brands build in the dark. With clear brand architecture, they’re building an ecosystem where every element reinforces competitive advantage.

Why is brand architecture important?

Here’s what most articles won’t tell you: brand architecture isn’t about making stakeholders feel organized. It’s about protecting and amplifying intellectual property value as brands scale.

1. Architecture protects IP value during expansion

When launching new offerings, entering new markets, or acquiring a company, the question becomes: Will this addition strengthen the brand or dilute it? Architecture provides the decision framework.

Disney didn’t randomly acquire Marvel, Pixar, and Star Wars. They evaluated how each property fit their architecture – all three built narrative universes that aligned with Disney’s core IP of storytelling and magic. Each acquisition compounded overall brand equity rather than fragmenting it.

Compare that to companies that acquire brands without architectural clarity. The brands sit in the portfolio like unconnected assets, creating confusion about what the parent company actually stands for.

2. Architecture enables strategic partnerships without dilution

Clear brand architecture makes partnerships possible that would otherwise fragment positioning. When PUMA partnered with Red Bull Racing, the strategic question was: does motorsport culture connect to athletic performance positioning?

The architecture provided the answer. Red Bull reinforced PUMA’s innovation and speed positioning. Porsche Design reinforced premium craftsmanship. BMW Motorsport reinforced German engineering heritage. Each partnership expanded the brand universe without diluting the core brand message.

Source: https://theproductionfactory.com/portfolio/redbull-racing-x-puma

3. Architecture guides M&A decisions

When LVMH acquired Tiffany & Co., they didn’t rebrand it as “Louis Vuitton Jewelry” and force it into the LVMH branded house. Why? Because Tiffany had its own brand equity and heritage. LVMH’s house of brands architecture allowed Tiffany to operate independently while benefiting from LVMH’s distribution and luxury expertise.

That’s strategic architecture. Knowing when to integrate and when to insulate.

4. Architecture creates compounding brand equity

This is where architecture moves from organizational tool to growth engine. When every sub-brand, product, and partnership reinforces the overarching brand’s IP, equity compounds. Each success lifts the entire family.

Nike doesn’t just sell sneakers. Every product release – Air Jordan, Air Max, Dunk, React – reinforces Nike’s athletic performance and cultural relevance positioning. The architecture ensures that whether buying running shoes or basketball jerseys, customers are buying into the same brand identity and value proposition.

What are the key components of brand architecture

Brand architecture isn’t just terminology. Each component plays a strategic role in how brand equity flows through a portfolio.

Master brand

The master brand sets the vision, values, and brand equity that flow to everything underneath it. It’s the North Star – the positioning and IP that defines what the organization stands for in the corporate hierarchy.

Nike is the master brand. Every product line – Nike Running, Nike Basketball, Nike Training – inherits Nike’s performance innovation positioning. The master brand does the heavy lifting of establishing trust. Sub-brands execute within that framework.

Strategic question: Is the master brand strong enough to carry the portfolio? If not, brands are building on shaky foundation.

Sub brands

Sub-brands (sometimes called sister brands) serve specific audiences or categories while leveraging master brand equity. They’re not independent – they’re brand extensions designed to capture market segments the original brand can’t reach alone.

Nike SB (skateboarding) serves the skate culture audience while operating under the Nike master brand because it borrows Nike’s performance and innovation equity. Skaters trust Nike SB partly because Nike is in the name and brings technical expertise.

Strategic question: Does this sub-brand need to exist, or could the main brand serve this audience? Sub-brands should unlock new value, not just organize existing products.

Parent brand

The parent brand is the corporate entity – the parent company that owns the portfolio. Sometimes it’s consumer-facing (Disney). Sometimes it’s invisible (Kering owns Gucci and Saint Laurent but most consumers don’t know that).

When VF Corporation restructured, they made a strategic choice: keep Vans, The North Face, and Timberland as consumer-facing master brands, use VF Corp as the corporate brand for portfolio management. This protected each brand’s unique positioning – skate culture, outdoor adventure, rugged workwear – from being diluted by corporate association.

Strategic question: Should the parent brand be visible or invisible? If corporate identity strengthens consumer brands, make it visible. If not, keep it behind the scenes.

Umbrella brand

An umbrella brand unifies disparate offerings under one brand identity. Patagonia is a strong example – Patagonia outdoor gear, Patagonia Provisions (food), Patagonia Action Works (activism platform) operate across different categories but share Patagonia’s environmental responsibility positioning.

The umbrella provides coherence. Without “Patagonia,” these would be unrelated businesses. With it, they’re part of an environmental, mission-driven universe.

Strategic risk: Umbrella brands work when the positioning unifies diverse service offerings. But if products are too disparate and don’t share values or audience, the umbrella dilutes instead of strengthening.

Understanding these key elements is the foundation for building scalable brand ecosystems that protect and amplify IP as brands grow.

Types of brand architecture

Brand architecture components work together in three primary types of brand architecture. But here’s what most guides miss: these models aren’t rigid categories. They’re strategic frameworks. The best brands use hybrid approaches tailored to business strategy, not textbook purity.

The goal isn’t to fit neatly into a model. It’s to build a structure that maximizes brand equity.

A branded house

Strategic intent: Leverage a powerful master brand across all offerings to create compounding equity.

In a branded house, the master brand leads. Every product, service, and offering carries the same brand identity. Think Nike, Adidas, Lululemon – the master brand is always visible, always the hero.

Real examples with strategic analysis

Nike built one of the world’s most valuable branded house examples in sports. Air Jordan, Air Max, React, Pegasus – every product reinforces “athletic performance meets cultural innovation.” When Nike launches new product lines or collaborations, it doesn’t need to build brand equity from scratch. The Nike swoosh transfers decades of trust and positioning instantly.

The branded house architecture creates efficiency. Nike markets one brand. Every product success strengthens the master brand, which strengthens future product launches. It’s compounding equity in action.

Lululemon proves the branded house model works for premium athletic wear. Lululemon leggings, tops, accessories, and now footwear and mirrors – the brand expanded from yoga pants into a lifestyle ecosystem. The expansion works because positioning is clear: technical performance meets mindful living. Every product inherits Lululemon’s premium wellness equity.

Adidas uses branded house architecture to own “sport meets street” across all categories. Adidas Originals, Adidas Performance, Adidas by Stella McCartney – the three stripes appear on everything from soccer cleats to fashion collaborations. Each line inherits Adidas equity while serving different audiences.

When to use a branded house

Use the branded house model when:

- Master brand IP is the competitive advantage

- Offerings share the target audience and core values

- Building a creator brand or founder-led company

- Marketing efficiency is essential (build one brand, not many)

Branded house works particularly well for creator brands and founder-led companies where personal IP – frameworks, methodology, perspective – is the competitive advantage. Building architecture around that IP enables scaling without dilution.

Benefits and challenges

Benefits:

- Efficient marketing strategy and spend (one brand to build)

- Compounding equity (every success strengthens the whole)

- Clear market positioning

- Easier for customers to understand

Challenges:

- No insulation from reputational damage

- Harder to target very different audiences

- The master brand must be strong enough to carry everything

- One misstep can damage the entire family

A house of brands

Strategic intent: Build individual brands that operate without connection to the parent company, allowing strategic flexibility and risk containment.

In a house of brands, each brand operates independently with its own brand identity. The parent company is invisible to consumers. LVMH owns Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, and Givenchy – most consumers have no idea they’re all under one corporate umbrella.

Real examples with strategic analysis

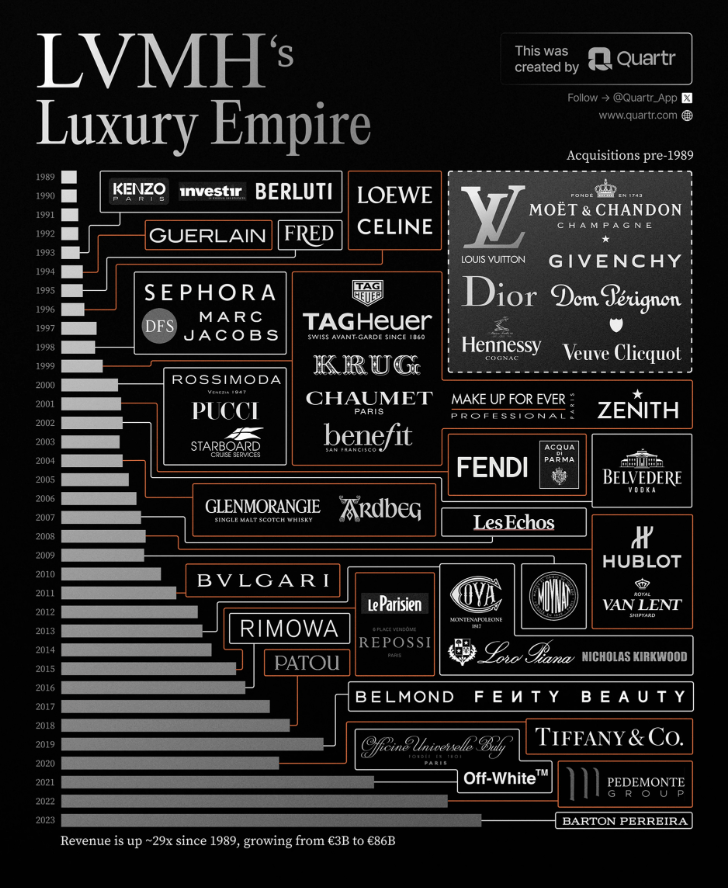

LVMH built a luxury empire on the house of brands model. LVMH owns 75+ brands across fashion, leather goods, watches, jewelry, and champagne – but the LVMH name never appears on products. Why? Because heritage and individual brand identity matter more than corporate association when buying luxury.

This architecture allows LVMH to own multiple positions in the same category. They have several luxury fashion houses (Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, Givenchy) each targeting different luxury segments with unique brand identities. If one brand makes a misstep, other brands aren’t affected.

Source: https://quartr.com/insights/edge/lvmh-guardians-of-tradition-engineers-of-desirability

VF Corporation uses a house of brands to segment the active lifestyle market with distinct identities. Vans targets skate culture. The North Face targets outdoor adventurers. Timberland targets rugged workwear. Dickies serves blue-collar workers. Each brand can position independently without the others constraining it.

Inditex keeps the corporate parent invisible across fast fashion. Zara, Massimo Dutti, Bershka, Pull&Bear, and Stradivarius each serve different demographics – from luxury-inspired fast fashion to teen streetwear. Most consumers don’t know Inditex owns them all.

When to use house of brands

Use house of brands when:

- Competing in the same category with different branded products

- Brands target vastly different audiences

- Risk containment is needed (one failure doesn’t damage other brands)

- Category matters more than corporate identity

- Acquiring brands with existing brand equity

Benefits and challenges

Benefits:

- Risk containment (brand failures are isolated)

- Strategic flexibility (each brand can pivot independently)

- Market coverage (own multiple positions in one category)

- Acquired brands keep their equity

Challenges:

- Expensive (building multiple brands from scratch)

- No shared equity between brands

- Complex brand portfolio management

- Marketing inefficiency (can’t leverage one brand’s success)

Endorsed brands

Strategic intent: Balance sub-brand independence with master brand endorsement to transfer equity while maintaining flexibility.

Endorsed brands sit between branded house and house of brands. Sub-brands have their own identity but carry the master brand’s endorsement – often as “by [Master Brand]” or through subtle visual cues in the endorsed brand architecture.

Real examples

Ralph Lauren perfected endorsed brands strategy in fashion. Polo Ralph Lauren, Ralph Lauren Collection, Lauren Ralph Lauren, Ralph Lauren Home – each brand has unique positioning (classic American, high luxury, accessible luxury, lifestyle) but “Ralph Lauren” or “Polo” endorsement transfers heritage and quality while maintaining different brand identities.

Source: https://www.ralphlauren.com

The endorsed brand architecture lets Ralph Lauren segment the fashion market by price point and occasion while sharing brand equity. A young professional might not afford Ralph Lauren Collection, but they trust Lauren Ralph Lauren because Ralph Lauren endorses it.

Giorgio Armani uses endorsement strategically across fashion segments. Giorgio Armani (haute couture), Emporio Armani (ready-to-wear), Armani Exchange (accessible fashion), Armani Casa (home) – each operates with unique positioning and price points, but “Armani” appears on everything. The flexibility allows Armani to transfer Italian luxury equity across market segments.

Jordan Brand demonstrates strategic endorsement. Air Jordan operates as a distinct brand with its own Jumpman logo, retail presence, and cultural identity in basketball and streetwear. But “Nike Air” technology and the Nike association add credibility. The architecture lets Jordan own basketball culture while Nike provides performance innovation heritage.

When to use endorsed brands

Use endorsed brands when:

- Acquiring brands with existing equity (don’t kill what was just purchased)

- Launching premium brand extensions of mass brands

- Expanding into categories where master brand adds credibility

- Flexibility to adjust endorsement strength is needed

This is common in M&A following industry trends. When acquiring a brand people trust, the goal isn’t to rebrand and destroy that equity. Instead, endorse it and transfer equity to it while letting it maintain independence.

Benefits and challenges

Benefits:

- Most flexible model (adjust endorsement strength)

- Sub-brands build equity while borrowing trust

- Works well for acquisitions

- Allows market segmentation with shared foundation

Challenges:

- Can confuse consumers if endorsement isn’t clear

- Requires active brand management of endorsement strength

- Sub-brands must truly be independent (not just renamed master brand products)

Brand architecture strategies

Types describe structures. Strategies describe how to implement and evolve them. This distinction matters because most successful brands don’t use one pure model – they use hybrid strategies adapted to business needs.

Disney is technically a branded house (Disney+ tells you it’s Disney). But Marvel, Pixar, and Star Wars operate with endorsed independence. That’s strategic, not confused.

Branded house strategy

When to implement:

- Building a founder brand or creator business where expertise is the product

- Strong master brand IP that transfers across categories

- Target audiences share values even if needs differ

How to execute:

Develop master brand identity first. Everything else inherits from it. Create sub-brand naming conventions that keep the master brand visible – Nike + product descriptor (Nike SB, Nike ACG). Maintain visual consistency across all offerings so every touchpoint reinforces the brand.

PUMA uses the branded house strategy for core apparel and footwear. Every collection, every product carries the PUMA formstrip. The master brand – athletic performance with street culture credibility – remains non-negotiable across all offerings.

Real application:

The key is knowing what’s flexible and what’s not. Nike allows product-level innovation (Air technology evolves) while keeping brand-level positioning rigid (athletic performance). That clarity prevents drift.

For creator brands and founder-led companies, branded house often works best. Personal IP – frameworks, methodology, perspective – is the competitive advantage. Building architecture around that IP enables scaling without dilution.

Endorsed brand strategy

When to implement:

- Acquiring brands with existing equity (don’t destroy what was paid for)

- Launching premium or value extensions that need distance from master brand

- Expanding into categories where master brand adds credibility but shouldn’t dominate

How to execute:

Determine endorsement strength. Does the master brand appear prominently (Polo Ralph Lauren) or subtly (Armani on Armani Exchange tags)? Let the sub-brand maintain unique positioning – that’s why endorsement is used instead of full integration. Use master brand to build credibility and trust without overwhelming sub-brand identity.

The strategic question: how much equity transfer is needed versus how much independence?

House of brands strategy

When to implement:

- Competing in the same category with multiple products targeting different segments

- Acquiring competitors and needing to maintain multiple positions

- Risk containment is needed (one brand’s failure shouldn’t damage other brands)

- Corporate identity adds no perceived value to consumer purchase decision

How to execute:

Build each brand independently with its own positioning, visual identity, and brand strategy. Keep corporate parent invisible – consumers shouldn’t know LVMH owns Dior and Fendi. Invest in strong portfolio management systems because managing multiple distinct identities, not variations of one, is complex.

This is expensive and complex, but it’s the only way to own multiple positions in one category or insulate brands from each other.

Hybrid brand strategy

Here’s the truth most brand architecture guides won’t tell you: most successful global brands use hybrid strategies. They don’t force model purity. They adapt architecture to business strategy.

Nike uses a hybrid model. It employs a branded house approach for core products (every shoe, every jersey carries the swoosh). But Jordan Brand operates semi-independently – its own Jumpman logo, retail stores, cultural identity – while still benefiting from Nike’s technology and distribution. Why? Because Jordan owns basketball culture in a way that needed independence, but Nike innovation adds performance credibility.

Source: https://www.nike.com/jordan

That’s not confused architecture. That’s strategically adaptive architecture.

Disney operates primarily as a branded house (Disney+ tells you it’s Disney). But when they acquired Marvel, Pixar, and Star Wars, they didn’t rebrand them as “Disney Marvel” or “Disney Star Wars.” They used an endorsed hybrid brand approach – these properties operate with independence while benefiting from Disney’s distribution and resources.

The architecture recognized that Marvel and Star Wars had brand equity Disney shouldn’t erase. But Disney’s ecosystem infrastructure (theme parks, merchandise, streaming) amplified that IP in ways the brands couldn’t do alone.

PUMA uses branded house for performance products but endorsed strategy for collaborations. Partnerships with Porsche Design and Red Bull Racing weren’t fully integrated PUMA products. They were collaborations where both brands showed – leveraging equity from both while creating something new.

The hybrid decision framework

Don’t ask “Which model should we use?” Ask:

- Which parts of the portfolio share audience and values? (Branded house)

- Which parts compete in the same category? (House of brands)

- Which acquired brands have equity that shouldn’t be erased? (Endorsed)

- Where does corporate identity add value versus create constraint?

The hybrid brand model isn’t a compromise. It’s strategic sophistication. The goal is maximum brand equity, not architectural purity.

How does brand architecture help companies?

Beyond organizational clarity, architecture drives strategic outcomes. Here’s what changes when structure is right.

1. Enables IP leverage across the portfolio

When Disney acquired Marvel, they didn’t just buy movie rights. They bought an IP system – characters, storylines, mythology – that could extend across movies, Disney+, theme parks, merchandise, gaming. Architecture determined how that IP flowed through Disney’s ecosystem.

Baby Yoda (Grogu) became a phenomenon because Disney’s architecture allowed one piece of IP to scale across streaming (The Mandalorian), merchandise (toys, apparel), theme parks (photo ops), and social media (memes, engagement). Without architecture, IP gets siloed in one channel.

2. Guides M&A decisions strategically for future expansion

When LVMH acquired Tiffany & Co., the strategic question wasn’t “Should we acquire it?” It was “How does this fit our architecture?”

LVMH’s answer: Tiffany doesn’t fit the fashion houses cluster, but it fits the jewelry maisons positioning. Solution? Keep Tiffany independent under LVMH’s house of brands architecture. Tiffany benefits from LVMH’s luxury expertise while maintaining brand independence and American heritage.

Source: https://www.tiffany.com/high-jewelry.html

Architecture answers: Does this acquisition strengthen the portfolio or fragment it? Should it be integrated or operate independently? Should it be rebranded or preserve existing equity?

3. Clarifies partnership opportunities

PUMA’s architecture made partnership decisions clearer. When Red Bull Racing approached, the question was: Does motorsport culture reinforce athletic performance positioning? Yes. Partnership approved.

When Porsche Design approached, the same question: does German engineering craftsmanship reinforce performance innovation? Yes. Partnership approved.

Architecture creates guardrails. Brands know what fits and what doesn’t because they know how partnerships need to connect back to core positioning. Without that clarity, partnerships become random sponsorship deals instead of strategic brand building with a compelling brand story.

4. Protects brand equity during expansion

Clear brand architecture prevents dilution. It defines what’s on-brand and what’s not. What markets can be entered and which ones would fragment positioning. What products strengthen the brand versus confuse it.

When a fashion brand launches activewear, architecture determines whether that’s brand extension (if athletic positioning exists) or brand dilution (if it doesn’t). The structure protects against opportunistic decisions that damage long-term equity.

5. Creates operational clarity

Teams need to know: Which brand voice should be used? Which visual identity? How should partnerships be co-branded? Where do marketing budgets get allocated?

Architecture answers those questions. It’s the brand’s framework and decision tool that keeps hundreds of people aligned as organizations scale.

How to create a cohesive brand architecture

Creating solid brand architecture isn’t a weekend workshop. It’s strategic infrastructure that requires research, alignment, and ongoing evolution. Here’s a framework for building architecture – informed by how brands at Disney, Warner Bros, and PUMA structured their portfolios.

Step 1: Audit your brand portfolio

Start with reality. Create a brand positioning map for every brand, sub-brand, product, and service owned. Assess brand equity for each – which ones have strong positioning? Which ones confuse customers? Where do overlaps exist? Where are the gaps?

This isn’t just listing what exists. It’s evaluating strategic value. Which brands drive equity? Which ones borrow it? Which ones dilute it?

Tool: Brand Architecture Checkup

Ask:

- Do customers understand how our brands relate?

- Do sub-brands strengthen or confuse master brand positioning?

- Is there competition against ourselves?

- Are there brands that should be retired or integrated?

- Where’s the equity concentrated?

Step 2: Define your strategic intent

Architecture follows brand strategy, not the other way around. Before choosing a model, answer:

Strategic questions:

- What’s the business strategy for the next 3-5 years?

- Will there be new brands, new products, or company acquisitions?

- Are there plans to enter new markets?

- Is there competition in the same category with different offerings?

- Do brands share target audiences and values?

- Is master brand IP the competitive advantage?

- Will brands with existing brand equity be acquired?

At Disney, the strategic intent was clear: build a family entertainment empire. That led to branded house for Disney properties and endorsed/hybrid for acquisitions (Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars) that had their own equity.

At PUMA, the intent was: own athletic performance with street culture credibility. That led to branded house for core products and endorsed strategy for collaborations that expanded into motorsport and fashion.

Architecture should enable strategy, not constrain it.

Step 3: Choose your architecture model(s)

Based on strategic intent, select the model – or hybrid combination – that aligns. Don’t force purity. Most brands use different approaches for different parts of the portfolio.

Decision framework:

- Same audience + shared values → Branded house

- Different audiences + different categories → House of brands

- Acquired brands with equity → Endorsed

- Complex portfolio → Hybrid (different models for different segments)

Document why this architecture was chosen. The rationale matters as much as the decision because strategy evolves and future teams need context.

Step 4: Create brand architecture guidelines

Architecture isn’t valuable if it lives in someone’s head. Document it.

Guidelines should include:

- Visual diagram showing brand relationships (master brand, sub-brands, product lines)

- Naming conventions (how sub-brands use master brand name)

- Logo usage rules (when to show master brand, when to show endorsement)

- Co-branding protocols (how partnerships work within architecture)

- Messaging hierarchy (which brand leads in different contexts)

- Decision criteria (what fits in portfolio, what doesn’t)

Make this accessible. At leading brands, brand guidelines aren’t locked in a PDF. They’re living documents teams reference constantly – especially when launching collaborations or entering new markets.

Step 5: Socialize and implement

Architecture only works if stakeholders understand and buy into it.

Implementation steps:

- Get leadership alignment (CEO, CMO, product heads need to champion this)

- Update all brand guidelines and templates

- Train teams on architecture decisions (why this was chosen, what it means for their work)

- Audit all touchpoints – website, packaging, marketing, partnerships

- Create governance process (who approves deviations from architecture?)

This is where many companies fail. They create beautiful architecture diagrams but don’t actually implement them. Teams keep making decisions without considering portfolio impact.

Step 6: Review and evolve architecture

Architecture isn’t permanent. It evolves with business strategy.

Review triggers:

- Annual strategy review

- Major acquisitions or divestitures

- New market entry

- Brand performance issues

- Leadership changes

Disney’s architecture evolved when they acquired Marvel and Pixar. LVMH’s architecture evolved as they expanded from champagne into luxury fashion and jewelry. Nike’s architecture evolved when Jordan Brand gained enough cultural power to warrant semi-independence.

The structure should enable growth, not freeze it.

Brand Architecture FAQs

How to make a brand architecture?

To make a brand architecture, start by auditing the current brand portfolio to understand their brand ownership and how brands currently relate. Define strategic business intent for the next 3-5 years (expansion plans, acquisitions, market entry). Choose the architecture model – branded house, house of brands, endorsed, or hybrid – that aligns with that strategy. Create documented guidelines showing brand relationships, naming conventions, and co-branding protocols. Implement across all touchpoints and review annually as strategy evolves.

The key is matching architecture to business strategy, not forcing a model because it’s trendy. If building a creator personal brand business, a branded house often works. If managing a portfolio company with multiple distinct brands, a house of brands or hybrid makes sense.

Working with a strategic partner who understands brand ecosystems helps if guidance is needed – architecture mistakes are expensive to fix once implemented.

What is the brand architecture of Coca-Cola?

Coca-Cola uses a hybrid brand architecture that combines elements of branded house and house of brands depending on the product line.

For Coke variants – Diet Coke, Coke Zero Sugar, Coca-Cola Cherry – they use a branded house model. All products carry the Coca-Cola name and inherit the master brand’s equity. These products target similar audiences and share core values, so the master brand leads.

For unrelated beverages – Sprite, Dasani water, Minute Maid juice, Powerade – Coca-Cola uses a house of brands model. These products operate with independent identities and minimal connection to Coca-Cola. Most consumers don’t know The Coca-Cola Company owns them.

The strategic rationale: Coke variants benefit from Coca-Cola equity. But Sprite targets different consumers with different positioning (lemon-lime, not cola), so independent branding makes sense. Forcing “Coca-Cola Sprite” would dilute both brands.

This hybrid approach lets Coca-Cola maximize equity where it helps and maintain independence where it doesn’t.

What is the difference between brand architecture and brand hierarchy?

Brand architecture is the strategic framework defining how all brands in a portfolio relate to each other – the organizing system that determines brand relationships, equity flow, and portfolio structure. It answers: How do brands connect? Which model is used? How does equity transfer?

Brand hierarchy specifically refers to the ranking or levels of brands within that architecture – the vertical structure showing master brand, sub-brands, and products. It’s one component of architecture, not the whole system.

Think of it this way: Architecture is the city plan. Hierarchy is the zoning map.

Example: Nike’s architecture is a branded house where the master brand leads all offerings. The hierarchy within that architecture is: Nike (master brand) → Product categories (Nike Running, Nike Basketball, Nike SB) → Product variants (Air Max 90, Air Jordan 1, Dunk Low).

Architecture is the broader strategic framework. Hierarchy is how brands stack within it.

What is the difference between brand architecture and brand portfolio?

Brand portfolio is the collection of all brands a company owns – the complete inventory of branded assets. It answers: What’s owned?

Brand architecture is the organizing structure and strategy defining how those brands relate to each other. It answers: How do they connect? How does equity flow? Which brands lead?

Portfolio is the inventory. Architecture is the organizing system.

Example: LVMH’s portfolio includes Louis Vuitton, Dior, Fendi, Givenchy, Tiffany, Moët & Chandon – 75+ brands across fashion, jewelry, champagne, and spirits. That’s what they own.

LVMH’s architecture is a house of brands where each operates independently with minimal connection to the LVMH parent brand. That’s how they’re organized.

Brands can have a large portfolio with poor architecture (brands that don’t connect strategically) or a small portfolio with strong architecture (brands that compound equity). A portfolio is about assets. Architecture is about strategy.

Build Architecture That Scales

Brand architecture isn’t organizational housekeeping. It’s ecosystem infrastructure that determines whether IP compounds or fragments as brands scale.

The brands that last – Disney, PUMA, Nike, Adidas – didn’t succeed by accident. They built strategic architecture that allowed intellectual property to flow through their portfolios, creating compounding equity where every product, partnership, and sub-brand reinforced the master brand.

Brands built at Disney, Warner Bros, Paramount, and PUMA over decades demonstrate how architecture decisions make or break expansion strategies. Clear structure enables partnerships, guides acquisitions, protects brand equity, and creates operational alignment. Poor structure creates confusion, dilution, and fragmentation.

The model chosen – branded house, house of brands, endorsed, hybrid – matters less than strategic alignment. Architecture should enable business strategy, not constrain it. It should protect IP while allowing evolution.